Akkad hasn't been going very far very fast at the moment. I scored a job teaching other people to write, so my own writing has been on hiatus. Things are calming down a bit now, so I'm back at it. Nothing much happens in Kigali over Christmas, so I'm going to lock myself away and type.

I've managed to bash out 4,000 words in the past two days, and I'm loving every minute of it. I get a tingly feeling from this one. I can usually tell when something's going to be good, and I think this will. It's sort of Borgias meets ancient Sumer.

I need to give a shout out to Leif Inselmann at The University of Göttingen, for patiently answering my questions - of which I have many. Leif is also an author writing German pulp fiction and science-fiction, some of it based on The Epic of Gilgamesh. You can find his website here and he's on Facebook here. I've been exceedingly lucky to find him as gaining expert support when writing is not always easy and it does make all the difference.

The research for this one is intense. It's further back in time than The Children of Lir, but because it was a written culture, whereas Ireland was oral, there's more known about it, so a greater number of slip-ups to make. This one's also straight historical fiction, rather than historical fantasy, so less artistic license available.

It really is a fascinating era. I knew that the story of the biblical flood was nicked from Sumerian legend, but I didn't realise Lilith, the snake and the apple tree were also in there. I think there's a bit of mythological oopsie-daisy going on. I remember Stephen Fry on an episode of QI mentioning that the Forbidden Fruit that Adam eats in the Bible is always depicted as an apple in paintings, but that it was never actually given a name in the Bible. This becomes interesting because, in Sumerian legend, the snake appears in the Huluppu tree as 'the serpent that cannot be charmed.' Scholars seem to agree that the Huluppu tree was a willow tree. However, there is another, very explicit poem, in which Inanna speaks fondly of her vulva and wanting it ploughed by several men, and at that point she is leaning back against an apple tree, which seems to become the symbol of female sexuality. Possibly where the idea of the serpent in the apple tree comes from.

Though, since visiting Armenia and seeing the veneration of pomegranates there, I've always harboured a pet theory that the forbidden fruit wasn't so much a symbol of sexuality, but the literal pomegranate, which was apparently the first fruit they made wine from in that region. As Christian says in Clueless, "You notice how wine makes people wanna feel sexy?" Combine that with in vino veritas and you have a recipe for rebellion against Christian social order. Sex, loss of inhibitions and a Bacchanalian sense of celebration.

You think it's perhaps overboard that they needed an entire story to stop people drinking, but stranger things have happened. In the 1200s a law had to be passed in France to stop people dancing in graveyards. What we do when we're free to do it, is anyone's guess.

Other things that have surprised me relate to European witchcraft and modern paganism. We associate witch dunking with the European witchcraft trials of the 1400s. This is where they tied someone to a chair, threw them in a pond and, if they sank, they were innocent but dead, but if they floated, which you always do on a wooden seat, they were a witch and therefore also dead - but dry. Anyway, that apparently also dates back to ancient Sumer, where it was used to weed out sorcerers.

In modern paganism there's something called 'skyclad,' which are rituals conducted naked. The idea behind it today is that you were born naked, and the naked body is to be celebrated. It's also a sign of coming before the gods humble, without trappings or finery. Apparently, same in ancient Sumer. The priests and priestesses conducted their rituals naked, with a fair bit of ritual sex thrown in for good measure.

I was just taken aback at how very much came from Sumer. Not just the flood, but the resurrection-from-death story, the Greek spring and winter divide of Persephone, the purple robes of Rome, and, possibly my favourite brain bomb moment...

Those who have read Rosy Hours, might remember that I talked about Nowruz, the Iranian New Year that happens at the spring equinox. It lasts for twelve days, with the thirteenth day being Sizdah Be-dar, the Day of Chaos. Which, today, coincides with April Fool's Day. The idea being that the only way to protect yourself from chaos is to create even greater mischief. It is the Day Between Years, the moment between the old year and the new.

So, fascinatingly enough, the Sumerians had a festival called Zagmuk:

...which literally means "beginning of the year", is a Mesopotamian festival celebrating the New Year. The feast fell in December and lasted about 12 days. It celebrates the triumph of Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon, over the forces of Chaos, symbolized in later times by Tiamat. The battle between Marduk and Chaos lasts 12 days, as does the festival of Zagmuk. In Uruk the festival was associated with the god An, the Sumerian god of the night sky. - Wikipedia

So, that gives us our twelve days of Christmas, but the Akkadians had a festival called Akitu, meaning 'head of the year', which was similar in nature and lines up with modern-day Nowruz and the vernal equinox.

I just thought this was fascinating.

There's so much going on here. So many things that are so familiar and yet many other things that it's hard to navigate with authenticity as they're so alien. Especially where sexuality is concerned. My story takes place long before the Code of Hammurabi comes into being in the early 1700s BC. The code really was a pivotal point in women's freedom and especially freedom of sexuality. Although it was codifying commonly held morals at the time, it set in stone that women were the property of their fathers and husbands, and also solidified the eye-for-an-eye style of revenge.

From around this point, goddesses gave way to gods, ending up with the paternalistic figurehead of Judeo-Christian and Islamic religions, which are both so young in the history of human beliefs.

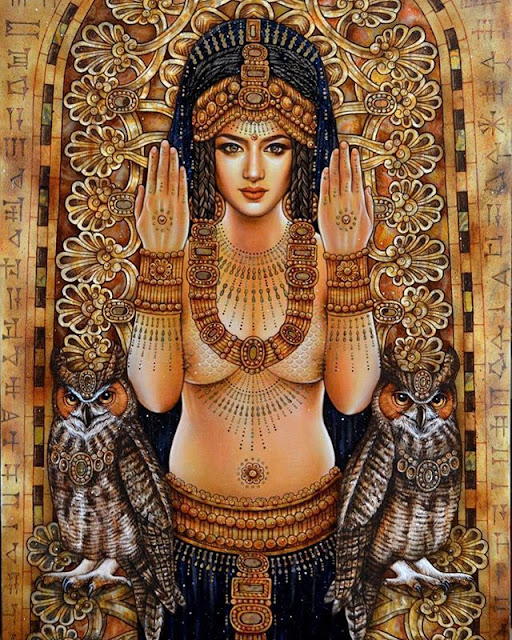

In the time of ancient Sumer, sex in the street was not uncommon, women slept with strangers as a holy act, and temples were full of prostitutes. The patron goddess of prostitutes (Ishtar/Inanna) was one of the most revered goddesses in the lands, and rightly so.

Meanwhile, the Euphrates and Tigris rivers that made the Fertile Crescent what it was, were orgasmed into being when Enki, the creator god, masturbated. In tribute, men would climb into the river to masturbate on holy days to ensure the crops. I just hope they warned anyone washing their clothes downriver.

I find all of this fabulous. You think you know what a culture is about, then it throws you a curveball. A bit like in The Children of Lir, when I learned about the pissing competition women had in the snow to prove their attractiveness.

Every day is just a new discovery with this book. Stuff I wish I'd known years ago. Of course, it's a balancing act between telling a good story and writing a historical textbook, but I'm really enjoying this one.